P&S Paving Puts Down Dry Process Plastics Pilot

BY AsphaltPro Staff

When a customer came to P&S Paving, Daytona Beach, Florida, in 2020 with the idea to add recycled waste plastics to the hot mix asphalt (HMA) for an upcoming parking lot project, Director of Quality Control Tim Carter was intrigued.

He was familiar with the use of recycled waste plastics in asphalt via the wet method, where a plastic additive is blended into the asphalt binder as a polymer modifier or percentage replacement at the terminal. However, he was less familiar with the use of recycled waste plastics via the dry method, where a plastic additive is added directly into the mixture at the asphalt plant as a mix modifier, binder modifier, aggregate coating, or aggregate replacement.

Carter said the dry method offers an affordable way to introduce recycled plastics at the plant while being able to control the rate directly.

“Up to this point, the use of plastics has overwhelmingly occurred at the terminal,” Carter said. “As the contractor, I’d just order the binder with [the plastics/polymers] already blended and suspended in it.” To utilize the wet method at the plant would require equipment that is often cost-prohibitive, he added. That’s why the dry method, which offers an affordable way to introduce recycled plastics at the plant while being able to control the rate directly, captured Carter’s interest. P&S Paving took up the challenge.

Plastic Pilot

The pilot project took place at a commercial center parking lot near Flagler County Municipal Airport in northeastern Florida. The engineer on the project wanted to repave the parking lot with 1.5 inches of a 9.5 mm Superpave mix with 1% recycled waste plastic by total weight of binder. Carter began researching the dry process P&S hoped to use and discovered a product called NewRoad®, by NVI Advanced Materials Group, that had been tested at the National Center for Asphalt Technology (NCAT) test track in 2020.

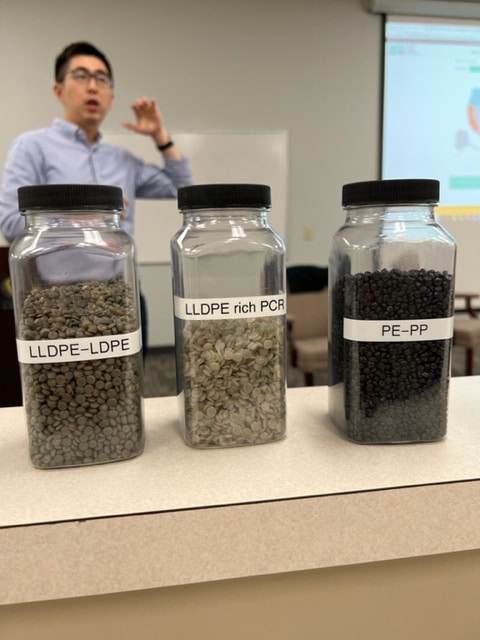

“The U.S. has a surplus of waste plastic materials of different varieties, but not all are good for use in HMA and warm-mix asphalt (WMA),” Carter said. NewRoad, the product P&S decided to use, is categorized as a high-density polyethylene (HPDE) and is similar in size and shape to “the beads kids use to make homemade jewelry,” Carter said. “Only they’re all black and made of engineered recycled plastics.”

NewRoad®, by NVI Advanced Materials Group, is categorized as a high-density polyethylene (HPDE). Photo courtesy of NVI

Carter said there are a number of ways to meter the plastic beads into the mix, including adding them into the RAP collar manually via a conveyor system with a hopper, or with a fiber machine. P&S opted to use its Hi-Tech Asphalt Solutions Model 9000 fiber machine, manufactured in Mechanicsville, Virginia, to feed the plastic into its pugmill.

When P&S invested in an Astec Double Barrel XHR plant back in 2015, Carter knew the pugmill would be integral to the plant’s ability to produce high recycled asphalt pavement (RAP) mixes (up to 65%), but has since discovered its value to the process of adding recycled plastics.

“Our fiber machine works on a blower system and blows the material [into the pugmill] at a calculated rate,” Carter said. To calibrate the rate, Carter timed how long it took to blow a set amount of the beads into a 55-gallon drum. “To achieve 2% of total binder content required metering in 7 pounds per minute at 200 tons per hour, our production rate for this project.”

The mix design for the pilot was designed at P&S’s lab and was a 9.5 mm TLC Superpave design using 45% RAP (40% coarse, 60% fine), with 5.5% liquid AC PG52-28 with recycled plastic beads equal to 1% of total binder content. Although P&S only added 1% for this project, Carter said his research reflects rates ranging from 1 to 10% worldwide.

Over the course of three days, P&S produced 743 tons for the pilot project at target temperatures between 300 and 315 degrees Fahrenheit. The melting point of the particular plastics P&S used is between 200 and 250 degrees Fahrenheit.

“That lower melting point makes sure they’ll integrate into the asphalt,” Carter said. “There are a variety of engineered recycled products, but we wanted one that would melt well for both HMA and WMA mixes.”

For instance, Carter continued, plastic from water bottles has a higher melting point than the plastomer and elastomer plastics Carter investigated. “Not all plastic is created equal. If you tried to add plastic from those bottles in this same way and expect it to integrate perfectly, you probably won’t be very successful.” However, he added, ongoing research is being done on effective methods to use a variety of waste plastics at NCAT in Auburn.

Professor Fan Yin explains recycled plastics use in HMA to the ACAF Specifications Committee at the NCAT facility in March 2022 with bottles of polymers in the foreground. Photo courtesy of Tim Carter

“We all know plastic production has increased exponentially in recent years and is causing mass pollution,” Carter said. Adding appropriate types of recycled plastic to asphalt mixes in the correct proportions and with proper methods not only diverts that waste from the landfill, but could potentially offer a number of benefits. “Not only does the recycled plastic increase bond strength, but it also offers high rut and crack resistance and can be used as a binder replacement for anywhere between 2 and 4% of the liquid AC in your asphalt mix design while still achieving quality performance,” Carter added, citing testing from NVI Advanced Materials Group.

Different Plastic, Different Goals

According to NVI Lead Engineer Andrew LaCroix, there are many ways to use recycled waste plastics in asphalt, from getting a better bond to replacing virgin aggregate. “Our focus is on performance, versus using as much plastic as possible,” he said.

That’s why NewRoad tends to be at the lower end in terms of dosing, at 2 pounds per ton of asphalt for a total of 0.1% weight of the total mix. “A little bit goes a long way, when you’re focusing on the performance side of things,” LaCroix said. When plastic is used as an aggregate replacement, dosages range from 3 to 5%, on average, he added. “[Proper dosing] is based on the type of performance you’re trying to get from adding plastics to asphalt.”

P&S incorporated NewRoads into the 743 tons for the pilot project near Flagler County Municipal Airport at 2% of total binder content.

For improved strength and flexibility, NVI’s objective for NewRoads, LaCroix said polyethylene is the category of plastics most often used. “Polyethylene tends to be milk jugs, laundry detergent bottles, and other thicker bottles,” he said. Ultimately, the type of plastic used is mostly a matter of melting temperature, LaCroix said. While some plastics melt at 200 degrees Fahrenheit, others require temperatures of 300 degrees or higher. “We want our products to melt at 250 degrees Fahrenheit or below, so our contractors can use it in warm mix and it still blends well.”

Plastics for NewRoad are mainly post-industrial plastics (90 to 95%), with the remainder coming from post-consumer sources. “Eighty percent of plastic waste is post-industrial,” LaCroix said, which is why so much of the recycled waste plastics in NewRoad come from this category. “We also prefer to work with post-industrial recycled plastic because it tends to be more consistent, cleaner and easier to deal with.”

Post-industrial waste plastics might include recycled products that don’t meet the manufacturer’s requirements, for example, during start-up and shut-down, mistakes and misprints of various plastic products, from bottles to plastic films. “By using that in NewRoad, we prevent it from going into the landfill.” One pound of NewRoad is equivalent to 50 water bottles or 100 plastic bags, so the full 1,500-pound tote in which NewRoad is sold is equivalent to 75,000 water bottles or 150,000 plastic bags. Or, by another measure, a 2-inch overlay uses 150,000 bottles or 300,000 bags for one lane-mile.

P&S Paving is based in Daytona Beach, Florida.

Although the use of material otherwise bound for the landfill is important, so too is the performance of the mix into which plastics are added. “Many times, the use of NewRoad reduces rutting by half [on the Hamburg Wheel test],” LaCroix said. On a job with the Iowa DOT, for example, LaCroix said adding 2 pounds of NewRoad per ton resulted in 4 mm rutting compared to 8 mm without NewRoad.

In terms of crack resistance, a 2017 trial project for the Iowa DOT also shows promising results. “They’re seeing hairline cracks in the wheel path of the control section, but the NewRoad section hasn’t seen any cracking,” LaCroix said, “so it seems to be creating better bonds and holding things together quite well.” Although NewRoad’s crack resistance performance on the IDEAL-CT test has shown varied results leaning toward a moderate increase in crack resistance, NCAT saw a 15 to 20% increase in crack resistance when it performed some testing of NewRoad for NVI.

“The most challenging part of [using recycled waste plastic in asphalt] is when the contractor is evaluating it in the lab,” LaCroix said. “Usually, they just mix the samples until the aggregate is thoroughly coated, which usually takes only a minute, but we recommend they mix it for five minutes to better simulate what’s happening at the plant and ensure they won’t see any plastic chunks that would have thoroughly blended in the more aggressive mixing environment of the asphalt plant.”

When P&S invested in an Astec Double Barrel XHR plant back in 2015, Carter knew the pugmill would be integral to the plant’s ability to produce high recycled asphalt pavement (RAP) mixes (up to 65%), but has since discovered its value to the process of adding recycled plastics.

Innovate to Operate

The latest asphalt technology is a topic of particular interest to Carter, who is also the chairman of specifications committee for the Asphalt Contractors’ Association of Florida (ACAF). “I’m very interested in where our industry is headed and what we can be doing differently,” Carter said. In that role, he frequently discusses new ideas with colleagues in the paving industry and officials at the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT). “The ability to embrace new technology is something I will personally be pushing as an agenda item.”

Although he’s only been in the role for a year, he’s already made important headway. One such victory was a change to FDOT’s smoothness specification. “It used to be that if you had smoothness deficiencies during the structural asphalt phase of paving, you’d have to create a 100-foot patch (50 feet on each side), which resulted in two additional joints,” Carter said. “Now, the contractor is able to choose a corrective method, within reason, so that when we get to the friction course, we still end up with a high quality pavement but are able to get there more efficiently and with decreased cost.”

One example would be the use of a milling machine to repair not only high areas, but also low areas. “That was a huge paradigm shift for a long-time complaint among contractors that has enabled us to gain more control over how we ultimately deliver a quality product to the department.”

More recently, FDOT issued a District Construction Engineer (DCE) memo in June 2022 to allow for a temporary increase in the amount of RAP that can be added to polymer-modified mix. Although FDOT doesn’t have a set RAP limit for unmodified mixes so long as they meet all volumetric properties, the department does have a limit for polymer-modified mixes. “Over the years, it’s increased from 20%, to 25%, to 30% last year,” Carter said.

“With the supply chain issues we’re facing nationally and our inability to sustain regular shipments of aggregates from out of state, the department has listened to our cries for help and has issued a new DCE memo to allow up to 40% RAP in polymer-modified mixes,” Carter said. “It’s only temporary, but this provides us an opportunity to gather data as we produce this mix and test its performance in real life settings so we can use that information for continued discussions in the future.”

Carter said he also hopes to gather more data on the performance of dry process recycled waste plastics for HMA and WMA and plans to do several more pilot projects in the next 8 to 12 months. “Ultimately, I’d like to see this [dry process] integrated into the state DOT system, but in order for that to happen more research needs to be done,” he said. “I’ve talked quite a bit to top officials in the DOT materials department and they’re very aware of this idea. And if the DOT starts to allow the use of recycled plastics, we might also begin to see that idea take hold at the county and city level.”

Whether enabling contractors to select a rideability repair method, increasing RAP limitations, or investigating methods to integrate additives at the plant, Carter said he is passionate about ways to give contractors in the state of Florida more control.

“There are old ideologies that limit the contractor’s control over this or that, but the relationship between contractors and the DOT was different back then,” he said. “Now, we have a much stronger partnership, a much better understanding of the mechanics of asphalt, and a lot of educated people in our industry and technology on our side.”

“We’ve come a long way,” Carter said. “Now, we need to be able to spread our wings and try new things in order to produce better quality pavements.”