Three Steps to Sustainable Machines

BY AsphaltPro Staff

To equal the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of a single Tier I 1990s-era piece of construction machinery would require 25 Tier IV 2021 machines, said Jeremy Harson, construction market director at Cummins, Columbus, Indiana.

Alongside experts from several other original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), Harson participated in a recent webinar presented by the Diesel Technology Forum on innovations to reduce construction equipment emissions.

“There are two ways to reduce emissions,” said Ray Gallant, vice president of sales support for Volvo Construction Equipment, Shippensburg, Pennsylvania. One, he said, is getting more production out of each gallon of fuel. The other is investing in cleaner fuels in the first place.

Get More Per Gallon

“We’ve looked at how the subsystems of the engine can be optimized and then how the engine is optimized inside the machine at a system level,” said Fred Rio, worldwide product manager of the construction digital and technology division at Caterpillar, Peoria, Illinois.

Alex Freitag, vice president of engineering at Bosch North America, Farmington Hills, Michigan, explained how Bosch has reduced emissions at the powertrain level through extended software functions, improved turbocharging, improved fuel injection, efficient temperature management and adapted exhaust-gas treatment, to name a few.

Harson said Cummins has also strived to reduce emissions while balancing this goal with customer value. He gave an example of Cummins’ B6.7 engine, which has reduced emissions dramatically from 1996 to 2019 while also increasing its peak power from 175 horsepower to 325 and improving fuel efficiency by 5 to 15 percent in that same time frame. Between the release of its Tier IV B6.7 engine and its Performance Series (2019) B6.7 engine, Cummins claims it has been able to achieve 9 percent more peak power and 30 to 40 percent more torque capability.

Zooming out to the entire machine, OEMs have invested in improved idle management. Jon Gilbeck, manager of production systems, site development and underground at John Deere, Moline, Illinois, estimates idle time can range anywhere from 5 to 40 percent in some applications.

That’s why Deere has equipped its machines with auto idle, auto shut down and ultra low idle features, which not only reduce emissions and fuel consumption but also result in less maintenance for the contractor. “If you’re not running, you’re not racking up hours, which is a way to extend that maintenance interval,” Harson said.

The next step after optimizing each piece of equipment individually, Rio said, is to “take all the machines together on a job site and look at how we can optimize the way those machines interact with each other so we have a more efficient operation.”

For example, during a case study comparing Cat Connect technology and services to traditional practices to pave a road, the Cat Connect job was able to reduce project hours by 46 percent, man hours by 31 percent, and equipment hours by 34 percent. This reduced fuel consumption by 37 percent.

“The greenest kilowatt is the one you don’t use,” Rio said. “If we can be more efficient, we can be greener and more profitable at the same time.”

Cleaner Fuels

Currently, Gallant said, combustion engines account for the vast majority of construction equipment in operation. As we move toward 2050, he anticipates that combustion engines will increasingly run on alternative fuels. He also expects battery electric equipment and fuel cell electric equipment to each grow to more than one-third market share.

“It’s really a matter of the duty cycle and power you need for each machine to get that particular job done,” Gallant said. For example, he added, battery electric drives will be well suited for compact machines, while heavier machines might be more suited for hybrid models with zero emissions fuel, and ultimately fuel cell and alternative fuels like hydrogen.

“Certain applications are more appropriate for electrification,” Freitag said, for example, daily usage below 250 miles. “If you start going into construction equipment and long haul equipment where usage and load are increased, hydrogen fuel cell powertrains would be more favorable.”

However, electrification could be useful for the growing use of smaller construction equipment, like skid steers, compact track loaders and compact excavators. Gilbeck said these small machines have seen a compound annual growth rate of 10 percent for the past 10 years as job sites have become increasingly mechanized and labor continues to be a pressing issue.

Rio said he thinks electrification will either require automation or some level of process automation (like software) to determine when to charge which machines and for how long. “Today’s diesel tanks are designed to allow for full shift, whereas the technology for electrification at least in the beginning may not allow for a full shift, especially in heavier applications,” Rio said.

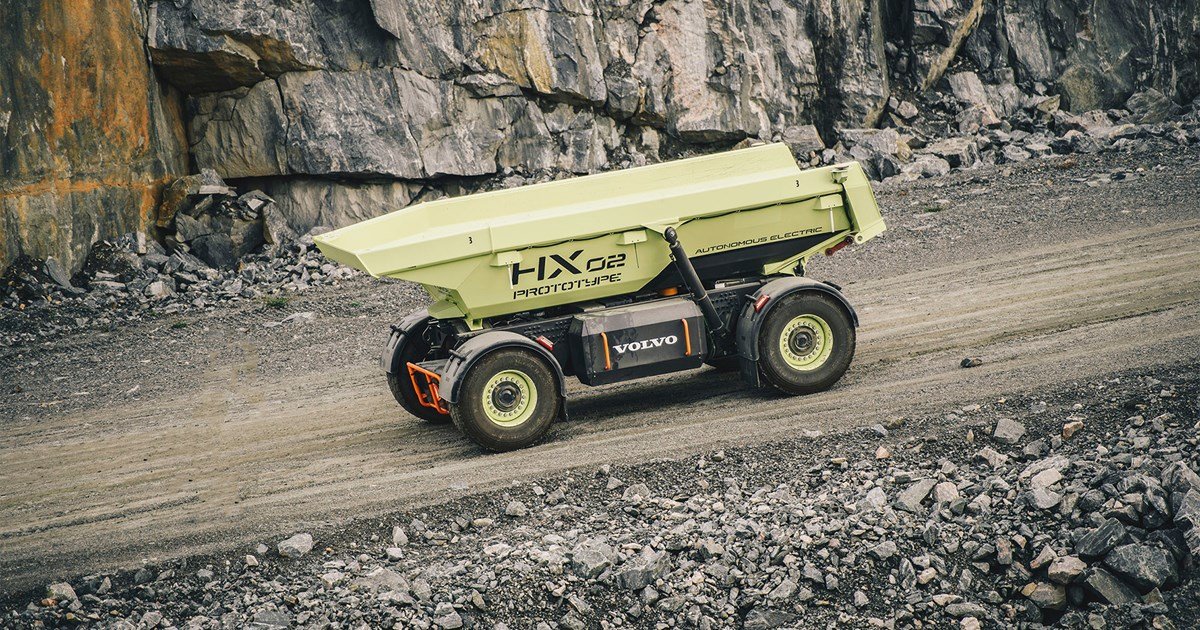

This could be seen in action during a 2018 research project by Volvo CE and its customer, Skanska, to electrify a quarry in Sweden. They were able to reduce CO2 at the site by 98 percent, energy cost by 70 percent and operator cost by 40 percent by replacing four 40-ton haulers with eight electric autonomous haulers. The autonomous haulers ran eight-minute dump/load cycles, with one minute per cycle to recharge at a quick charge station. In the future, Gallant said, this would be an ideal use case for induction charging.

The Path Forward

“It took 100 years to build our petroleum infrastructure,” Harson said. “It’s going to take some time to move from diesel.” He anticipates another generation of advanced diesel equipment to be released at the end of this decade and a “rational, gradual phase-in” of equipment running on alternative power solutions.

“It’s going to take time for that infrastructure to develop and those technology costs to come down,” Harson said. “A lot of the equipment we’ve talked about today is what will be tasked to build that infrastructure.”

Furthermore, OEMs have to keep customers in mind. “They’re not necessarily getting paid more for buying an electric machine or using alternative fuel,” Gilbeck said. That’s why each OEM discussed how, alongside emissions reductions, today’s equipment also offers reduced cost of ownership and improved performance.

As the infrastructure develops and costs for alternatively powered equipment come down, Harson said we can expect to continue to see reduced emissions from construction equipment year by year as a result of natural fleet turnover, given how much cleaner modern equipment runs compared to previous generations.

“On-road equipment typically has 10 to 15 years of machine life,” Gilbeck said, while off-road equipment is often in operation for up to three times as long as on-road machinery. “As we think about policy changes and the solutions we put in place today, we have to recognize that the solutions that are in the market today will be there for quite a long time.”