A Woman of Asphalt: Meet TxDOT’s Brenda Guerra

BY Sandy Lender

With skills in highways, project estimating, construction, site inspections and traffic control, Brenda Guerra has achieved success as a woman of asphalt. Guerra attained her associate degree in science at Palo Alto in 2002 and her bachelor degree in civil engineering at The University of Texas at Austin in 2005. She joined the asphalt industry shortly after graduation. Her career trajectory included design and construction, and she now serves as the district maintenance engineer for the Texas DOT in the Austin District.

“I started out as an engineer-in-training, learning how to use the software. There is a young engineers program in the DOT, so after five years of design, I was rotated to construction. The 18 months I spent in construction was very eye-opening; made me think of things I didn’t think of in design.”

Brenda Guerra

Now with that background and experience, Guerra leads the Austin District four-year pavement management plan for 11 counties and was willing to share specific challenges she and her team have met head-on for other women in the industry to learn from. For example, she encourages women to take initiative when they see the right opportunity to do so.

“Working in a state agency, there are still some unestablished S.O.P.s. If I see there’s something not headed in the right direction, I will raise a flag. Don’t be shy or scared to ask the wrong question; go ahead and ask your question. Don’t just sit back.”

Guerra also worked in area offices, where she felt comfortable asking questions, learning and leading different efforts because she had good leadership mentoring her.

One of the mentors she gives credit to is Miguel Arellano, deputy district engineer, previously director of operations and pavement engineer. “He handles policies in our district now. He is a bright person who sees solutions. If I have an issue, I want to talk to him about it.

“I had some great supervisors. Teamwork is so important. In my teams, we put everything on the table. You have to resolve disagreements or put away differences of opinions and don’t be afraid to make decisions.”

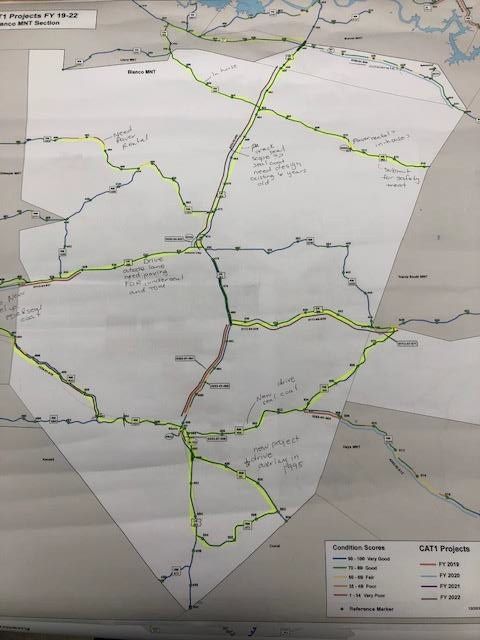

The four-year pavement management plan that Guerra manages begins with field visits of 15 maintenance sections.

In 2020, as district maintenance engineer, she got to lead the four-year pavement management plan. This process takes teamwork Guerra is a proponent of.

The four-year pavement management plan that Guerra manages begins with field visits of 15 maintenance sections.

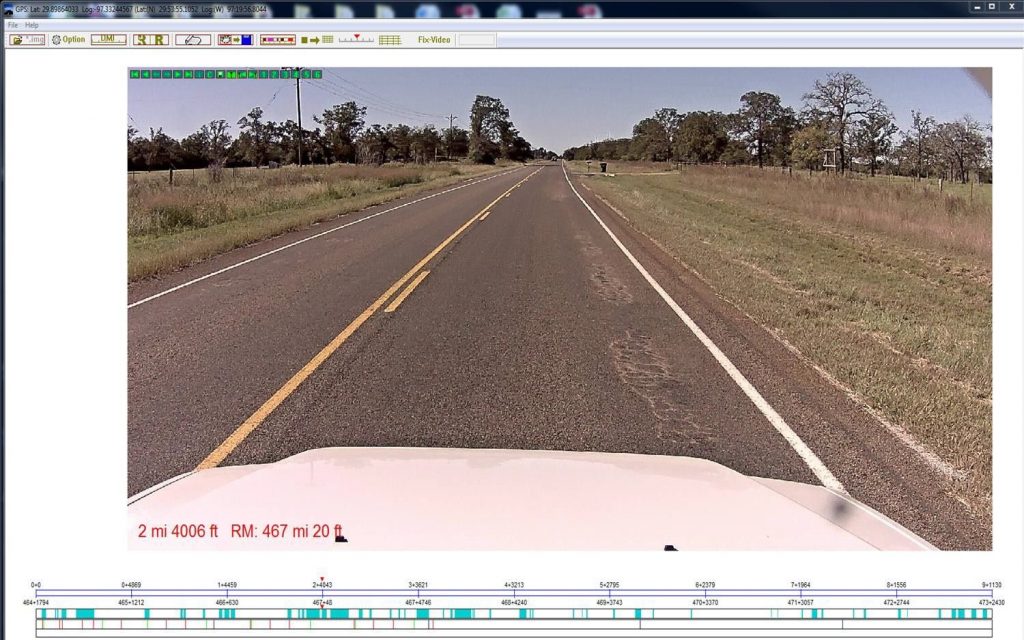

“A four-year plan starts with field visits of 15 maintenance sections who drive the areas daily. They handle routine maintenance like fixing potholes and sealing cracks. Our section reviews the pavement scores for the previous year. We identify critical sections for the fiscal year based on observations and data. To do this, we jump in the truck and look at the areas that the area engineers and maintenance supervisors are concerned about.

The four-year pavement management plan that Guerra manages begins with field visits of 15 maintenance sections.

“Pavement scores come in in February; we meet in March. We have an asset manager Hui Wu who is super smart; she developed a tool to rank the scores and pavement needs so when we met in March, we have a list.

“At our meeting, we scope the work. We try to build more pavement structure. We try not to remove much. We follow up after the meeting to request estimates for each location identified. My team reviews the estimates to make sure they include everything including safety items. We are designing for safety. All the information and budget are then turned over to the director of operations for yearly allocations; so this has to be revisited every year. Ultimately, the director has to present the plan to administration.”

If that sounds like a lot of responsibility, it is. But listening to Guerra explain the process and discuss the efforts of her team make it obvious she has enormous respect for the position and the players involved.

“When it comes to pavements in general, I think there’s some perception that it’s not as important or as sexy as vertical construction, but it is important. We have more lane miles of asphalt. They think it’s just oil and rock, but there’s so much more to it. There’s so much more to it than the surface, too.

“Binder, mix, design—we have to build it correctly. We need to train our inspectors on placement.”

She agreed that our industry has the perception of being a “dirty job,” but it’s a gritty necessity. “In a way, it’s true. I remember getting my hands dirty as an inspector. I was in the best shape of my life. We would crawl in these bridge girders—come out covered in rust. At the end of the day, your clothes weren’t so tidy. It was always great to work outdoors. It was great to work with your co-workers. I always got this sense of strength.

It was awesome working out in the field. We should really appreciate those workers out in the field because they’re out there breaking their backs.”