Proposed Bill Directs OSHA to Issue National Heat Standards

BY AsphaltPro Staff

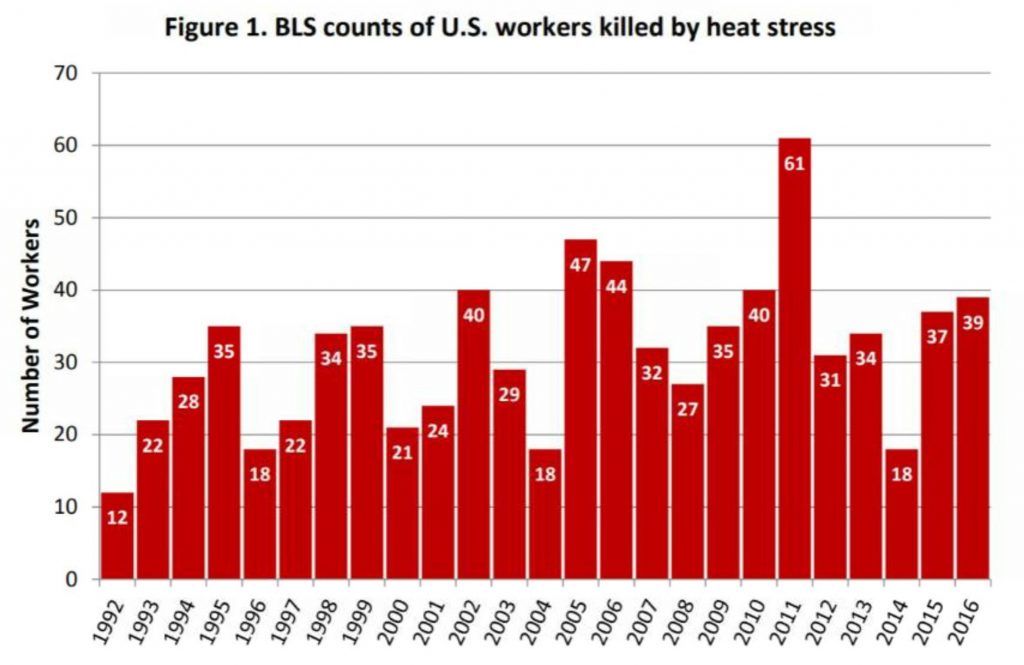

Between 1992 and 2017, 815 workers died and 70,000 were injured due to heat-related causes. According to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), more than 40 percent of heat-related worker deaths occur in the construction industry.

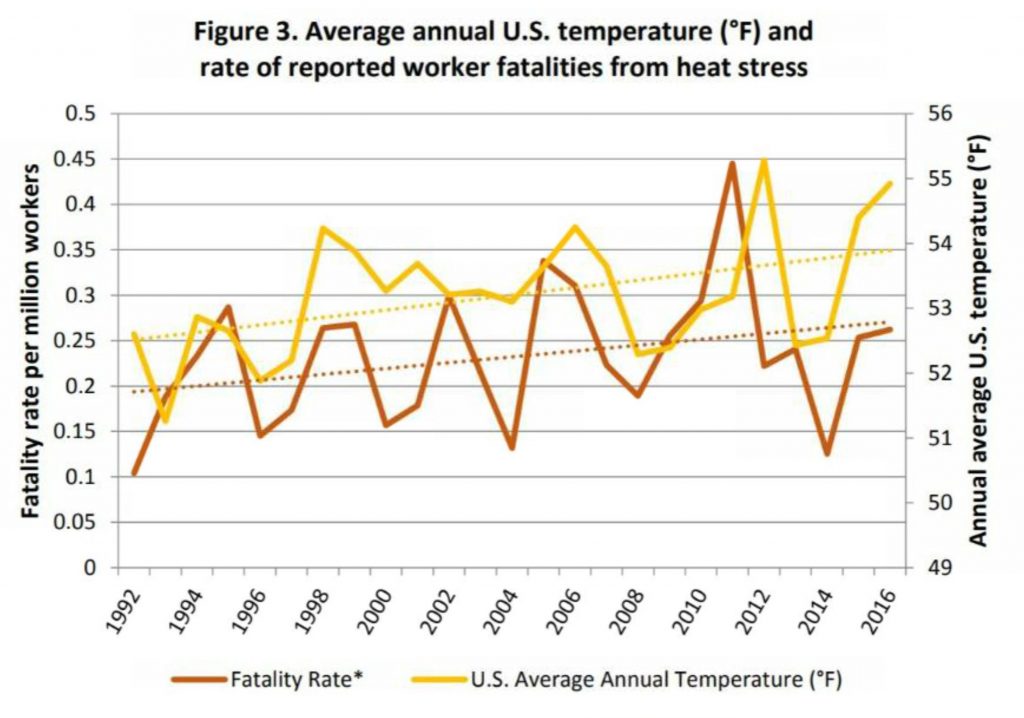

Due to underreporting, it’s likely there are a great many more instances of heat-related death and injury among workers throughout the United States. As average temperatures continue to increase year by year, the problem is expected to worsen.

Figure 1: BLS counts of U.S. workers killed by heat stress. Graph courtesy of the petition signed by more than 130 organizations requesting that OSHA issue a national heat standard. Source: BLS’ Occupational Injuries/Illnesses and Fatal Injuries Profiles.

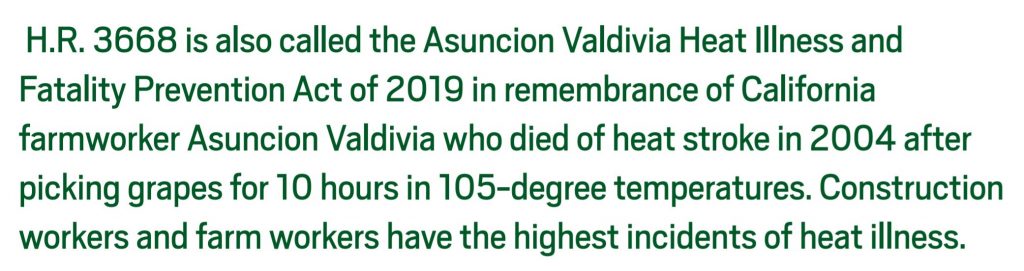

That’s why U.S. Congressional Representative Judy Chu (D-California) introduced H.R. 3668 July 10, 2019. The bill, if enacted, directs OSHA to issue a national standard to protect workers from heat-related injuries and illnesses.

Existing OSHA Standards

OSHA’s only standard pertaining to heat-related safety is its General Duty Clause, which states that employers are responsible for providing workplaces free of known safety hazards. “This includes protecting workers from extreme heat,” reads OSHA’s Heat Illness Prevention page.

OSHA’s existing approach to heat safety centers on its Heat Illness Prevention Campaign, launched in 2011. The campaign offers training, outreach events, and social media messaging related to heat safety under OSHA’s recommendations of water, rest, and shade. In 2015, the free OSHA NIOSH Heat Safety Tool app for Android and iOS was launched, providing hourly forecasts of heat index, heat risk level, and suggestions for precautions and first aid tips.

However, last year, more than 130 organizations, including farm groups, universities, labor groups and legal groups, co-signed a petition for OSHA to issue a national heat protection standard. The petition suggested the standard address mandatory rest breaks, personal protective equipment, shade, hydration, exposure and medical monitoring, employee training and heat alerts, among other measures.

Behind the Bill

In 1972, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) issued criteria for such a standard, which has since been updated in 1986 ad 2016. Multiple branches of the U.S. Armed Forces and several states have established heat prevention guidelines or standards.

For example, California’s heat standard was established in 2005 following a spike in heat-related worker deaths.

The standard requires employers to provide one quart of potable drinking water per worker per hour; monitor, and provide shade for, all employees on particularly hot days; provide rest breaks for employees upon request; and train new employees and supervisors on heat-related illness and preventative measures.

From 2013 to 2017, Cal-OSHA has averaged 1,416 citations for unsafe heat load conditions per year. In that same period, OSHA averaged just 28 heat-related citations per year, nationwide.

Figure 2: Average annual U.S. temperature (degrees F) and rate of reported worker fatalities. Fatality rate per 1 million workers, derived by dividing reports of fatalities by total U.S. employees in private sector and state and local governments. Graph courtesy of the petition signed by more than 130 organizations requesting that OSHA issue a national heat standard. Sources: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (temperature data) and BLS (fatality rate data).

Enforcement Ensures Safety

A 2016 study examining OSHA’s 84 heat enforcement cases in 2012 and 2013 found that only 16 percent of the employers used the daily heat index to identify potential heat risks. Less than half of the employers had any heat illness prevention program at all. One quarter did not provide employees water or limited access to it.

The study also found that 97 percent did not adjust work/rest schedules based on heat conditions and work intensity, and only one of the employers had a heat acclimatization program in place.

“The vast majority of heat-related workplace deaths and illnesses can be prevented by access to water, rest and shade,” reads the bill, echoing OSHA’s own Water. Rest. Shade. campaign. However, the bill continues, many employers don’t provide such simple measures of prevention.

A federal standard from OSHA could change that. If enacted, H.R. 3668 requires the final standard be announced no later than 42 months after the date of enactment.

It is vitally important to keep workers safe, whether or not OSHA enacts a national heat safety standard.

Overheated workers are not only at risk of heat-related illness, according to OSHA. Overheating also results in reduced concentration and physical ability, both of which increase the risk of other types of accidents. Additionally, heat may fog up safety goggles or prompt workers to shed valuable PPE.

Although keeping workers safe is the primary objective, these risks can also increase workers’ compensation costs and medical expenses. Additionally, heat-related illness decreases productivity.

Many states may be out of the woods for the 2019 paving season, but other states are still in the thick of it. Here are some suggestions, which may or may not become part of the national standard, that could help you keep employees safe.

Track More than Temp

Employers should monitor the heat index, which takes both temperature and humidity into account, to identify heat-related risks. OSHA has resources available on its website outlining how to use the heat index to keep employees safe. Generally, environments below 91 degrees Fahrenheit are considered low risk; 91-103, moderate risk; 103-115, high risk; and beyond 115, extreme risk.

According to OSHA, Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT) is even more accurate to measure heat hazards than the heat index, since it measures temperature, humidity, wind speed and radiant heat. The heat stress chapter in OSHA’s Technical Manual provides more. information

Water, Rest, Shade

Both environmental factors and job-specific factors can contribute to the likelihood of heat-related illness. Environmental factors include high temperature and high humidity, direct sun exposure, limited air movement, radiant heat sources and contact with hot objects. Job-specific factors include physical exertion and wearing bulky, non-breathable clothing.

Although we cannot control the weather, there is plenty we can control to help workers beat the heat. For example, shade canopies on equipment, cooling neck towels, or adjusting work schedules for cooler parts of the day or to accommodate frequent breaks in a shady environment. NIOSH’s recommendations also include a worker’s free access to water “in quantities sufficient to maintain adequate levels of hydration at varying levels of heat.”

The baseline is one cup of cool water every 15 to 20 minutes. NIOSH also recommends offering liquids that would replenish workers’ electrolytes, such as Gatorade, if they’ve been sweating for more than two hours.

Heat Acclimatization

Although all workers may be at risk, those who have not built up a tolerance to working in hot conditions may be at a greater risk. This can include new employees, but also those returning from time away and even seasoned workers in the event of rapid temperature changes, such as heat waves. Heat acclimatization can help.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, heat acclimatization is the “improvement in heat tolerance that comes from gradually increasing the intensity or duration of work performed in a hot setting.” NIOSH recommends workers beginning work in high-heat environments, or those who will be working in hotter conditions than normal (for example, during a heat wave) be gradually acclimatized to the work over a period of seven to 14 days.

Train, Communicate, Plan Ahead

NIOSH also recommends that employers train all employees and supervisors on prevention and mitigate heat risks.

Additionally, employers should communicate heat-related hazards and the dangers of heat stress to all workers as they arise. NIOSH also recommend implementing a heat alert program to inform workers of heat waves so that they can be aware and prepared.

Throughout the shift, workers should be monitored for signs of illness. Should an emergency occur, every crew should have a plan in place.

Track & Protect

Take time to track and analyze data on any heat-related incidents on your crews so you can take measures to prevent repeat occurrences. If an employee or supervisor reports potential risks, NIOSH reminds us to protect these whistleblowers.

We should all want to keep our employees and our fellow crew members safe!

For more tips to beat the heat, check out the following articles on www.theasphaltpro.com: “Stay Cool During Summer Paving,” “Wear Sunscreen When Working Outside,” and “7 Hot Weather Safety Tips for Construction Workers.”