How New OSHA Noise Limits Could Affect Your Crew

BY AsphaltPro Staff

In May, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) published its spring semiannual regulatory agenda, which included potential changes to acceptable noise levels and solutions in construction work zones.

“When OSHA noise regulations were crafted in the 1970s and 1980s, the construction industry was specifically exempted from the broader general industry standards,” said Brad Witt, director of hearing protection for Honeywell Safety Products. “This was due to unique conditions within the industry, such as a transient workforce, changing worksites and intermittent noise levels that are very task-dependent.”

As a result, OSHA limits noise exposure to 85 decibels over an eight-hour period for employees in manufacturing and service sectors, but caps noise exposure at 90 decibels over an eight-hour shift for the construction industry. This limit of 85 decibels for an eight-hour shift is also recommended by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

OSHA also requires that workers of all industries who are exposed to hazardous noise levels be included in a hearing conservation program. However, OSHA requires certain standards for hearing conservation programs for general industry, such as annual audiometric testing, “But in the OSHA standard for construction, no such requirement exists,” Witt said.

Changes to noise regulations for the construction industry could affect a variety of areas, from noise limitations to employer responsibilities.

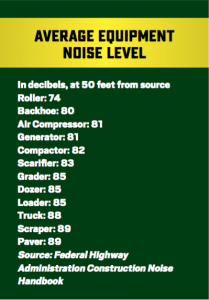

According to the Federal Highway Administration’s Construction Noise Handbook, the average paver runs at 89 decibels, and the average truck, 88 decibels. Changes of even a few decibels could require some changes for asphalt paving crews.

According to the Federal Highway Administration’s Construction Noise Handbook, the average paver runs at 89 decibels, and the average truck, 88 decibels. Changes of even a few decibels could require some changes for asphalt paving crews.

“OSHA has long desired to update the noise standard for construction to provide more guidance to employers in terms of hearing conservation,” Witt said, adding that several models at the state level have proven quite effective in reducing workplace hearing loss.

Some states, such as Washington, have already mandated more stringent noise standards. Washington limits construction employees’ exposure to 85 decibels over an eight-hour shift. In 2004, a worker’s compensation report showed that construction workers, which made up 7 percent of the state’s workforce, filed 21 percent of all accepted worker’s compensation hearing loss claims.

Loss of Hearing, Explained

According to the Bureau of Labor statistics, noise-related hearing loss is one of the most prevalent occupational health concerns. Loud noise can also make communication difficult, as well as make it hard to hear warning signals, such as backup alarms.

Signs that a workplace may be too noisy include hearing ringing or humming or experiencing temporary hearing loss after you leave work, and needing to shout to be heard by a coworker an arm’s length away, according to OSHA.

“One of the best indicators of noise damage is to take a hearing test regularly,” Witt said. However, thus far, “it’s up to workers to take the initiative to monitor their own potential hearing loss.”

Even a small change in the number of decibels results in a significant difference in volume. For example, a vacuum produces 70 decibels, while a chain saw produces 120 decibels. However, 120 decibels is actually 32 times louder than 70 decibels.

OSHA mandates that for every 5-decibel increase above the required limit, the amount of time a person can be exposed would be cut in half. NIOSH recommends a 3-decibel exchange rate, so every increase of 3 decibels above the required level halves the recommended exposure time.

For example, if OSHA limited noise exposure of construction workers to 85 decibels—the average volume of a milling machine—to eight hours, it would limit exposure to a jackhammer at 100 decibels to only one hour. NIOSH’s 3-decibel exchange rate would allow 8 hours near the milling machine, but only 15 minutes near the jackhammer.

What Would It Mean?

In November, OSHA will be requesting information to gauge how effective and feasible a lower noise standard would be in the construction industry. Depending on that information, a variety of new requirements could potentially come to light.

Employers may be required to reduce noise levels to new limits, either by enclosing the noise source or placing a barrier between it and the employee, buying quieter equipment and properly maintaining and lubricating the equipment, rotating employees from louder jobs to quieter jobs, providing quiet areas, or restricting worker presence to a certain distance away from noisy equipment. According to the OSHA website, hearing protection is another option that is “acceptable, but less desirable” than other solutions.

Employers may be required to reduce noise levels to new limits, either by enclosing the noise source or placing a barrier between it and the employee, buying quieter equipment and properly maintaining and lubricating the equipment, rotating employees from louder jobs to quieter jobs, providing quiet areas, or restricting worker presence to a certain distance away from noisy equipment. According to the OSHA website, hearing protection is another option that is “acceptable, but less desirable” than other solutions.

Although hearing protection can reduce noise to lower levels, it comes at a risk.

“While the main concern with hearing protection is too little protection, it’s also critical to avoid overprotection—the earplugs or earmuffs are blocking noise so well, that critical communication or warning signal detection is impaired,” Witt said. “In a paving operation, with constantly moving equipment and hazards coming from a variety of directions, a worker who loses situational awareness is a safety liability.”

“When employees are exposed to high levels of noise, OSHA requires employers to provide hearing protectors and to train their employees to wear them correctly,” said Tim Chismar, technical service specialist with 3M. “Failure to do so can lead to noise induced hearing loss, OSHA fines and increased insurance costs. The reality of the situation is that many employers go out and buy the highest level of hearing protection available thinking that they may be erring on the side of caution.”

If employees are exposed to noise levels beyond OSHA limits, employers in the construction industry could be required to follow more stringent hearing conservation programs, specifics of which could include measuring noise levels, providing free annual hearing exams, as well as training and evaluations of hearing protection.

Find the Right PPE

According to Witt, it’s important to offer your employees the right hearing protection solutions from the start so they’ll be more likely to wear them. He first suggests determining the best hearing protector for the situation.

“Where noise levels are extremely high and continuous, most workers find conventional foam earplugs to be the most comfortable,” Witt said. “They are excellent noise-blockers when they are inserted correctly (deeply), and they are comfortable enough to be worn all day.” This type of protection also only requires a few seconds of preparation—roll down, pull back the ear, insert and hold.

For short-term noise, Witt recommends banded earplugs or earmuffs. “They can be quickly inserted for short-duration exposure, like saw cuts or brief power tool use, and then can hang conveniently around the neck when not in use,” he said. However, banded earplugs don’t block as much noise as foam earplugs, as they aren’t inserted as deeply into the ear canal.

“Convenience is the main benefit of banded earplugs, as a hearing protector is more likely to be worn when it’s readily available.”

Witt recommends reusable earplugs for intermittent noise sources. “Ease of insertion is the main benefit of these earplugs,” he said. “They have the added benefit of being ideal for dirty-hands environments. The worker inserts them by pushing on a stem, without touching any part of the earplug that goes inside the ear.

“Dirty hands are the norm in a paving operation, so a roll-down foam earplug might not be the best choice,” Witt said of hearing protection that would need to be used multiple times throughout a shift. He recommends a pre-molded earplug with a stem, or a push in earplug like Honeywell’s TrustFit Pod.

Another key component of choosing the right ear protection is ensuring a proper fit.

“A number of hearing protector manufacturers now provide fit-test systems, training aids, posters and video tutorials to ensure workers understand how to properly fit their protection,” Witt said. “The goal is not simply to pass out earplugs. The goal is to protect the worker, so that nobody needs to leave the job with less hearing than when they arrived.”

To verify protection levels, Honeywell offers VeriPRO, which allows workers to check the fit of any earplug from any manufacturer. He also suggests offering a variety of sizes to provide options to your crew that are both comfortable and do not interfere with hard hats and eyewear, which can “break the acoustic seal” of hearing protection.

A very important last piece of the hearing-protection-as-PPE puzzle is maintaining communication and situational awareness with earplugs or earmuffs in place.

Other members of the crew may not require communication capabilities. For these employees, level-dependent earmuffs will allow them to maintain situational awareness while offering protection.

Innovations in Noise Reduction

“In the past, it was not uncommon to hear workers say, ‘I don’t wear the earplugs because I’d rather lose my hearing than be hit by a hazard I didn’t hear coming,’” Witt said. “Fortunately, hearing protector manufacturers have responded with a variety of styles and features that take this into consideration.”

“There are no magic valves that block hazardous noise but allow ‘good noise’ to pass through,” Witt said. However, there are a few hearing protection options that try to manage sound while still offering workers much-needed situational awareness.

The two options Witt suggests are passive hearing protectors and electronic protection. Passive speech-friendly earplugs have filters or design features that give them a very flat frequency response, allowing speech and warning signals to be heard more naturally, Witt said. “Here’s an analogy: A stereo will often have both a volume control and a tone control. A conventional earplug reduces both volume and tone, by clipping the high frequencies of the surrounding noise, making understanding speech difficult.” However, a speech-friendly earplug “turns down” the volume without affecting tone control, Witt said. “Speech sounds more natural, and warning signals are more audible.”

The second suggestion, electronic protection, is level-dependent.

“When noise levels are relatively quiet, surrounding sound is slightly amplified in the earmuff to optimize situational awareness,” Witt said. “But as soon as surrounding sound reaches hazardous levels, the earmuff circuitry instantly detects and adjusts to optimize protection. In an environment with fluctuating noise levels, that kind of balance between protection and situational awareness is critical—and we now have hearing protectors that can do both.”

“The bottom line of these technological advances means the paving crew worker does not need to sacrifice hearing in order to keep situational awareness,” Witt said.

According to Chismar, this type of hearing protection is already popular in hunting and shooting sports circles, as well as with law enforcement and the military. Level-dependent electronic hearing protection is available both as earmuffs and in-ear devices.

“Level-dependent hearing technology can be great for environments where there are intermittent loud sounds, such as in the construction industry,” Chismar said.

The 3M level-dependent earmuffs are also equipped with volume control, so any quieter noises can be amplified by up to around 10 decibels. The earmuffs’ electronics can also be turned off to provide traditional hearing protection.

3M also provides other hearing protection and communication solutions, like two-way radio and Bluetooth® capabilities, and AM/FM radio, as well as many combinations of these options. For example, the paver operator, dump man and haul truck driver may want to use level-dependent hearing protection that also offers two-way radio communication so they can coordinate mix delivery. Alternatively, the foreman might want hearing protection that offers Bluetooth® compatibility so he/she can talk on a mobile phone without having to leave the noisy environment.

3M also provides other hearing protection and communication solutions, like two-way radio and Bluetooth® capabilities, and AM/FM radio, as well as many combinations of these options. For example, the paver operator, dump man and haul truck driver may want to use level-dependent hearing protection that also offers two-way radio communication so they can coordinate mix delivery. Alternatively, the foreman might want hearing protection that offers Bluetooth® compatibility so he/she can talk on a mobile phone without having to leave the noisy environment.

“Many times falls, struck by, and eye injuries are the first priorities for construction companies as those hazards may seem more immediate,” Chismar said. “However, noise-induced hearing loss has been one of the most widespread occupational health concerns for the past few decades. When hearing protection is needed on the job site, selecting the most appropriate hearing protector for the application is critical for worker compliance and protection. Newer technologies, such as level-dependent hearing protection and wireless communication, may require a higher upfront investment, but these types of protectors can help improve a worker’s situational awareness and ability to communicate, which may ultimately help to improve the safety and productivity of the work crew.”

A Case Study on Today’s Job Site

According to Paving Superintendent Ray Eisner, crewmembers in Martin Marietta’s Denver Metro Paving Division are already required to wear hearing protection. However, this is part of the company’s policy, not an OSHA requirement.

“Most of our crews actually prefer [the hearing protection],” Eisner said. They are presented with a variety of options for hearing protection at the beginning of each paving season. “We go through a lot of earplugs out there.”

To maintain communication on the job site, Eisner said it’s easy to hear someone talking near you, as long as you’re not right next to the paver. “If you’re too close to the paver, you might have to take one earplug out to be able to hear someone talking to you,” he said. Additionally, he said, his crew has had no issues hearing backup alarms and other audible warnings while wearing hearing protection.

The paver operator, dump man and Shuttle Buggy operator wear noise-suppressing headphones equipped with radios so they can continue to communicate effectively.

“They really come in handy when we’re paving at night, which we’re doing a lot of right now,” Eisner said. “During the day, though, they may wear them as needed, but they still use hand signals to communicate with each other, too.”

Eisner has noticed job sites getting quieter over time as equipment gets quieter. “I ran rollers for 17 years and they were noisier than heck, but now they’re a lot quieter and more comfortable,” he said. “The equipment has gotten significantly quieter, even just in the past 5 years.”

Look To The Future

Witt said that it’s important to note that any change to OSHA noise regulations would be a lengthy process with multiple levels of input and review. The agency plans to issue a request for information this November.

Noise Reduction Ratings

Most earplugs and earmuffs have a noise reduction rating (NRR) between 20 and 35 decibels. However, that doesn’t mean wearing earplugs with a 33-decibel NRR would reduce the sound of a paver running at 89 decibels to 56.

According to Tim Chismar, technical service specialist with 3M, although it’s possible for an individual to obtain the full NRR value and reduce the paver volume in our example from 89 decibels to 56, actual achieved NRR value will depend on a variety of factors.

“Due to many factors, such as selecting the proper size of protector, the variation of fit, fitting skill, and the motivation of the user, many people may receive less protection than the NRR value,” he said. “It’s important to understand that the NRR value is an accurate measure of noise reduction of a hearing protection device in a laboratory setting (as set forth in government standards), but not necessarily an accurate reflection of noise reduction for an individual user in a workplace setting.”

OSHA recommends taking the NRR number, subtracting seven and then dividing by two. For our previous example, that means those NRR 33 earplugs would conservatively reduce the paver’s noise to 76 decibels.

Equation:

(33 – 7)/2 = 13

(NRR # – 7)/2 = Noise reduction in decibels

“[That equation] is a derating method recommended by OSHA to help employers select adequate protection for their employees,” Chismar said. “In addition, 3M recommends fit testing of individual workers by their employers to validate that each worker receives an adequate level of protection.”

If your job site is louder than required limits, even with earplugs, your crew may be required to wear both earplugs and earmuffs. Earplugs generally cannot offer attenuation ratings higher than the mid-30s, due to physical limitations, reduction in comfort and general effectiveness.