Keathley Defines Striping Precision, Professionalism

BY AsphaltPro Staff

When Mike Keathley first opened Keathley Line Striping (KLS), LaVernia, Texas, three years ago, he used to mention to potential customers that everyone on his crew is deaf.

“We found that this kept losing us bids,” he said. “There is a stigma that comes with being deaf. People don’t understand what we can do and therefore become hesitant to allow us to submit a bid.”

KLS is a 100 percent deaf-owned and employed company. After facing this early discrimination, Keathley no longer mentions this to prospective clients.

“When customers call us, they are not asking us for a medical history,” he said. “They are asking us to perform a job so there is no reason to share that we are deaf. When we show up on a job site, whether we’re doing an estimate, a walk-through or performing the job requested, we find that people are blown away. They can see we are professionals and leaders in our industry.”

A Culturally Deaf Crew

When Keathley, a self-taught striper, began learning how to stripe, he realized there weren’t many resources available. So, he began creating his own library of training videos that are useful to both deaf and hearing people.

KLS has a crew of three and additional part-time staff as needed. Every member of the crew is culturally deaf, including Keathley. A person is culturally deaf if he or she has always been in a predominantly deaf environment. In Keathley’s case, he attended a deaf school, his children are deaf and most of his friends are deaf.

“I live in a world of sign language and closed captioning,” Keathley said. “The only time I interact with hearing people is when I go shopping or go to work.”

Although Keathley’s whole team is deaf, he doesn’t hire based on disability status. “I hire them because I know what they are capable of,” he said. “As a result, I am blessed to be able to provide an equal footing for a disenfranchised group of people.”

Having a deaf team also improves communication on the crew, which uses American Sign Language as its primary language. Furthermore, Keathley said he and his crew have a strong desire to prove its work ethic and overcome discrimination.

KLS exclusively uses Graco LineLazers and LineDrivers to perform its work. “They’re top of the line,” Keathley said. “We also enhance our stripers with the latest gadgets in order to help us perform our work in an efficient manner.”

“We always bust our butts and want to make our customers happy with our work,” he said. “Nobody has anything to fear by hiring deaf employees.”

However, KLS still regularly faces discrimination as a deaf-owned and operated business.

Recently, the company was awarded some work by a major industry player. While performing the work, a store manager became upset when the crew asked him to either remove his mask, so the crew could read his lips, or to write down what he was saying.

“He got very agitated that we could not understand him and kept yelling at us,” Keathley said. “I kept telling him we are deaf and that we can’t tell what he’s saying, but he became so agitated by this that I could do nothing but walk away and continue to finish our work.”

Roughly 80 percent of KLS’s work is parking lots.

Although the team finished the job and the customer was happy with the results, Keathley was shocked by their lack of understanding when it comes to communicating with deaf people. “What if another customer refuses to proactively communicate with me or my team?” he said. Although his company appreciated the work, it put Keathley in a difficult situation. “We cannot allow them to hold our disability against us as a condition of employment, so we chose to let them go as a customer.”

In another instance, a store manager insisted that Keathley’s team needed to have a hearing person on site while striping the facility. Keathley himself arrived on the job shortly after the manager’s request.

“When I introduced myself as the deaf owner of the company, the manager’s eyes got so big and he got so flustered,” Keathley recalls, but the manager remained adamant that they needed to have a hearing person on site. “He felt we needed to be supervised; he just didn’t know what deaf people can do.”

Every member of KLS’s crew is culturally deaf, including Keathley. Not only does this provide jobs to a disenfranchised group of people, Keathley said, but it also improves communication on the crew, which uses American Sign Language as its primary language.

The crew packed up and left, but Keathley didn’t quit. He reached out to the property owner who hired his company for the job, who was furious at the manager’s behavior. “The property owner had us return to complete the job and happily paid us for the extra time.”

“We know most people don’t maliciously discriminate,” Keathley said, “but people do discriminate and that nonsense needs to stop.”

Although the company battles audism from time to time, Keathley is heartened that many of his customers find their story uplifting and inspiring. “We actually get a ton of work from it.”

Safety Without Sound

Although the company battles audism from time to time, Keathley is heartened that many of his customers find their story uplifting and inspiring. “We actually get a ton of work from it,” he said.

Keathley reiterates that his company adheres to all OSHA rules and federal, state, county and city laws. He has generally modeled KLS to avoid work situations that would require him to obtain an exemption based on his crew’s disability. However, he knows how to handle these situations when they arise. For example, there is a hearing test required to obtain a Department of Transportation medical card, for which KLS was able to request an exemption from the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) since they are protected by the Rehabilitation Act of 1973.

The Rehabilitation Act prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability in programs conducted by federal agencies, in programs receiving federal financial assistance, in federal employment, and in the employment practices of federal contractors.

“Safety is paramount when working in active roadways and parking lots,” Keathley said, regardless of circumstances. KLS has invested in approximately 24 LED safety warning lights on its truck and enclosed trailer, and four on its line drivers, in addition to wearing bright colored reflective safety uniforms. However, Keathley recognizes that there are only so many safety products one can implement.

“We also run a crew that’s usually one man larger than the average striping crew so we have an extra set of eyes on our job sites,” he said. “We keep our heads on a swivel and we look out for each other.”

He’s also found this approach a bit easier because roughly 80 percent of KLS’s work is parking lots. Fifteen percent are unique jobs such as helipads, basketball courts, playgrounds, athletic fields, etc. Only 5 percent are roadways. “We’re not a long line striping company, so public roads aren’t a big part of what we do, but that could always change in the future as we grow,” Keathley said.

KLS exclusively uses Graco LineLazers and LineDrivers to perform its work. “They’re top of the line,” Keathley said. “We also enhance our stripers with the latest gadgets in order to help us perform our work in an efficient manner.” For example, its stripers are equipped with gun raisers to raise and lower the paint guns without getting off the machine. “I firmly believe we remain safer by keeping our butts in our seats, instead of getting off and fiddling around with our machines in an open parking lot,” Keathley said.

A Self-Taught Striper

Although people facing disabilities should not have to prove themselves any more so than others, Keathley has made the most of this circumstance and built a company known and respected for its performance and precision.

Before launching KLS, Keathley had been performing repair work for friends of his mother and sign language interpreters. When his mother passed away, Keathley struggled to find new work and began exploring the commercial market. However, he faced regular discrimination and rejection.

“On my last bid to a general contractor, I was basically told we had the job,” he said. “When I went to discuss the work with him, he ran me off and said he couldn’t be responsible for me. I was crushed. I had a kid on the way and no money. I walked out of that building destroyed.”

He sat down on a bench right out front and stared into the parking lot nearly in tears. “Then it hit me,” he said. He noticed that the parking lot in front of him needed striping, so he went home, looked up property tax records and mailed the property owner a letter. Soon, he got the job. “I had effectively eliminated the middle man and there was no need for anyone to feel like they had to be ‘responsible’ for me.”

Fifteen percent of the work KLS performs are unique jobs such as helipads, basketball courts, playgrounds, athletic fields, etc.

Although Keathley’s brother briefly striped parking lots many years ago, Keathley is a self-taught striper. But, as he learned, he noticed a lack of training resources.

“There isn’t much offered on how to learn to become a pavement markings specialist,” Keathley said. So, he began creating his own library of training videos that are useful to both deaf and hearing people. “The inability to hear is not the disability. It is the lack of access to language and information that is the real disability.”

The videos also improved his own performance. “I used to race motorcycles at the track and watching videos of our body position was critical to learning how to ride faster,” he said. “I applied that same logic to line striping.”

He would tape cameras to his striper and watch the videos over and over, improving each time. “Before I knew it, the videos started being shared and now people often turn to me for advice on how to line stripe.”

Mr. Fix-It

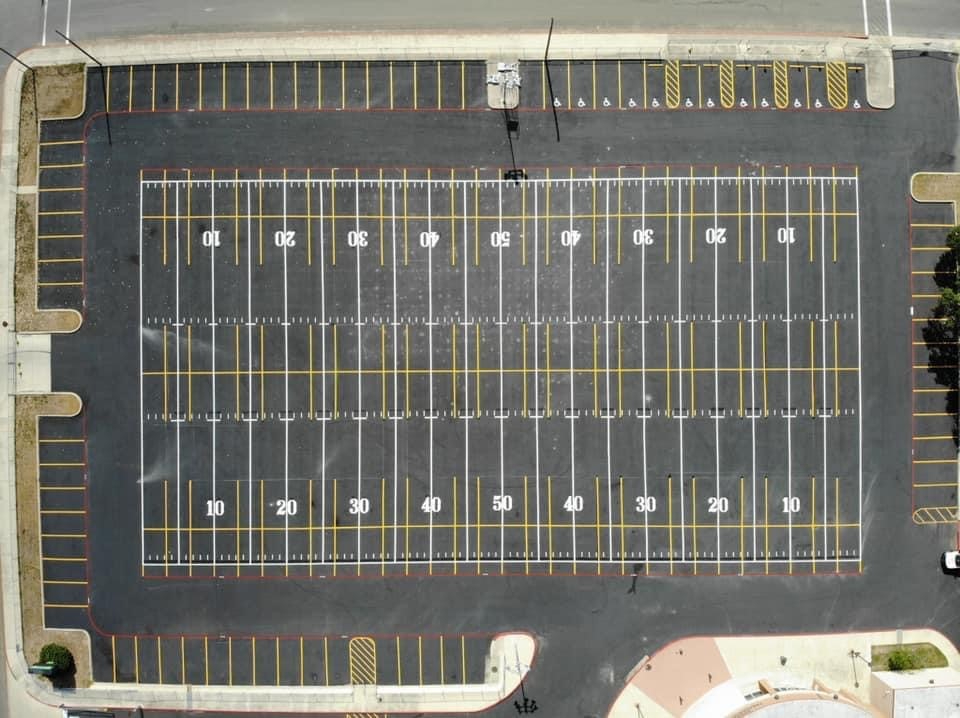

In the summer of 2020, Keathley received a call from a paving company KLS often works with, who asked Keathley to correct a striping project at a 5A high school in Texas that had been performed by another striping company. When Keathley showed up on the job, the prior subcontractor had done such a poor job that the paving company had to sealcoat the lot so KLS could start from square one.

The school had been facing a unique problem. It had a rich football tradition, as well as a competitive marching band. The football team held practice after school on the football field, but the band also needed the field to practice their formations.

The football field was right next to a large parking lot, onto which KLS striped a football field layout. “By day, it was a parking lot for students,” Keathley said. “By night, it was a practice field for the marching band.” It was a job that was easily fumbled by crews lacking KLS’s attention to detail.

One of the most unique jobs KLS has striped is at a 5A high school in Texas: “By day, it was a parking lot for students,” Keathley said. “By night, it was a practice field for the marching band.”

The job required a lot of thought and planning among Keathley, the school’s grounds keeper and its athletic director. “The biggest obstacle was making sure the lot was up to code after merging the football field grid onto the parking stalls,” Keathley said.

To do so, the crew used yellow paint for the parking stalls and white for the football grid. The fact that the parking lot is used by the same students day after day, who are familiar with the lines, also helps. They also had to take care to ensure that the fire lanes were clear. In total, the job required 120 gallons of paint.

Furthermore, all of this had to be done within a week, before the start of the school year. After pulling through for the school under tight deadlines, KLS maintains an active working relationship with that school district to this day. “The customer was very happy with our work, and it has led to many other opportunities within that school district,” Keathley said.

Although people facing disabilities should not have to prove themselves any more so than others, Keathley has made the most of this circumstance and built a company known and respected for its performance and precision.

“We are professionals in every sense of the word,” Keathley said. “We know what we’re doing. All we ask is that people let us do our jobs.”