How You Should Handle DEF

BY AsphaltPro Staff

Most paving contractors know exactly how to handle their equipment for winter storage. They know they need to apply lubricants, prepare the batteries and schedule maintenance and inspections.

What many of us may not know is how to handle our Tier IV equipment—both for winter storage and for general upkeep throughout the paving season. Many contractors still have questions and misconceptions about diesel exhaust fluid (DEF), especially about shelf life, winter weather procedures and general storage.

“There are a lot of lingering questions about DEF in the marketplace,” said Luke Van Wyk, general manager of Thunder Creek Equipment. For example, expired DEF and contaminated DEF can harm the catalytic converter in your engine. But, that isn’t something an operator can see.

“Most operators don’t know how these new systems work,” Van Wyk said. “They just see the light on the dash come on telling them to refill the tank. But they don’t know how the material is handled inside the tank.”

For example, Van Wyk was at a jobsite where the crew picked up discarded jugs and bottles to use to store DEF.

“There are still a lot of questions about the proper handling of DEF,” he said. “We need to address these issues now instead of years down the road when contractors are paying for the things they don’t know now.”

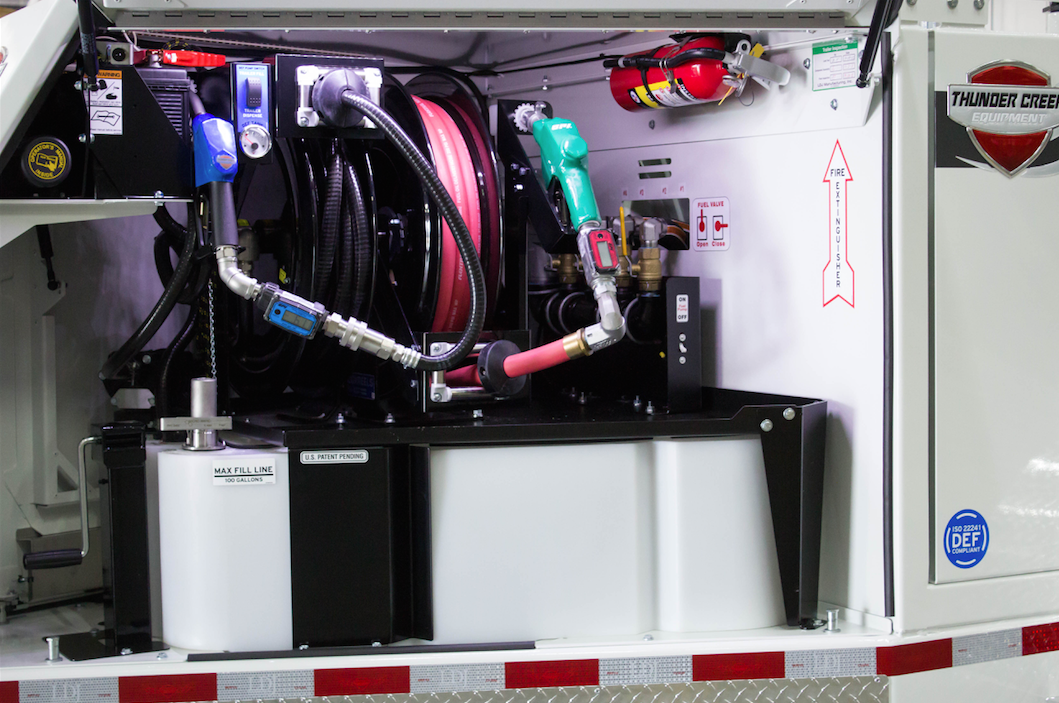

A two-in-one enclosed DEF system on a fuel trailer, like you see here, is one way to avoid contamination of your DEF.

What is DEF?

Diesel exhaust fluid, or DEF is 32.5 percent pure automotive-grade urea and 67.5 percent de-ionized water.

“That’s all it ever is,” Van Wyk said. “There are no additives and no different blends to take it away from that spec.”

Unlike urea used in the agriculture industry in fertilizers, the urea in DEF has no preservatives. “If the urea in DEF had preservatives, it would cover the catalytic converter in a gummy material,” Van Wyk said. The absence of that preservative gives DEF a shelf life of 36 months in climates where the average ambient temperature is 60 degrees Fahrenheit or below, and six months in places where average ambient temperatures are above 95 degrees. “With prolonged exposure to heat over long periods of time, the water will begin to evaporate and take the DEF out of spec.”

“Some people think DEF is like milk, that’s it’s only good for a couple of weeks,” Van Wyk said. “In many cases, shelf life isn’t an issue.” Another common misconception is that freezing temperatures will harm the DEF, but Van Wyk said freezing doesn’t affect the shelf life or the chemistry of the DEF. “It will freeze at 12 degrees Fahrenheit,” he said. “But that just turns it from a liquid into a solid and it expands by 7 percent.”

That expansion creates some concern that it could harm the equipment system, but Van Wyk said most, if not all, systems are engineered to manage this.

“Most DEF systems flush the DEF from the aftertreatment system back into the tank every time you turn the key off,” Van Wyk said. “In almost every case, that tank has been built with joints to withstand that expansion.”

For example, said Jon Sjoblad with Caterpillar, Cat machines purge DEF from the aftertreatment system every time the engine is shut down. “Every time the engine is shut off, the pump will reverse and pull all the DEF from the aftertreatment system and lines back into the tank.”

Additionally, like most equipment, Van Wyk said original storage containers are built to expand with the DEF. However, intermediate handling systems may not be designed to automatically flush DEF from the system back into the tank. In this case, operators may need to manually flush DEF from the pumps, hoses and nozzles before winter storage to avoid ruptures after DEF expands.

When storing your equipment over winter, Van Wyk said it isn’t necessary to drain the DEF, but cautions that it is always important to refer back to your equipment manufacturer’s guidelines.

When contractors need to refuel more than a couple Tier IV Final machines, single-use 2.5-gallon jugs simply won’t cut it. One hundred gallon closed DEF systems outfitted on a diesel trailer, like you could see here, offer a bulk storage and refueling solution.

How to Handle DEF

If DEF exceeds its shelf life, Van Wyk warns that it will become less effective.

“We use DEF to reduce nitrogen oxide,” he said. When urea is sprayed into the exhaust system, it turns into ammonia, which will break down the NOx into water vapor and nitrogen. “If the urea isn’t as potent, it’s going to take more DEF to get that NOx output down to the levels the engine is programmed to get it to.”

It can also cause degradation of the catalytic converter. “If the DEF is contaminated, what can happen over time is that urea can start to break down the reactive coating of the catalytic converter,” Van Wyk said.

However, using DEF beyond its shelf life isn’t a very common concern. Van Wyk said it’s far more common to see contractors using contaminated DEF rather than expired DEF. The number one cause of this contamination is improper handling.

“Keeping DEF contaminant-free is paramount,” Sjoblad said. He recommends storing it only in its original container to prevent cross-contamination and making sure the DEF container and machine tank area are dust-free before transferring, adding that Cat machines are equipped with a series of strainers and filters as added protection against debris contamination.

“The biggest challenge we’ve seen is contractors buying larger packages of DEF and refilling small containers, like oil jugs, and antifreeze containers—you name it—with DEF,” Van Wyk said. “That introduces contaminants into the DEF.”

Those contaminants become an issue because, over time, they will build up on the catalytic converter and the urea will begin to corrode the contaminants, which will rust the catalytic converter, Van Wyk said.

“You may not see the effects immediately, but you will see them down the road,” he said. “It’s like salt on your car. Eventually, your car is going to rust.”

To combat this issue, DEF should only be handled in sealed or closed containers or systems. Two and a half gallon jugs and drums are sealed containers intended only to be used one time, and then disposed of. Larger containers of DEF, such as 275- and 330-gallon IBC totes, can be reused because they are designed with a closed point for filling and emptying the container. Although he estimates that less than 10 percent of the off-highway industry’s fleets are Tier IV-compliant at this time, that number will only increase as old equipment is retired and new equipment is purchased.

“The natural progression we see is when contractors only have a couple machines that require DEF, they buy the 2.5-gallon jugs,” Van Wyk said. “As they acquire more Tier IV equipment, they’re going to buy DEF in larger and larger quantities, but should always be sure they maintain that closed system.”

He equates it to handling beer. “When the beer comes out of the keg, you have a tapper. You don’t just open the keg,” he said. “We need to handle DEF in the same way.”

That’s where contractors need to discover new solutions.

“Fuel and DEF go hand-in-hand like peanut butter and jelly,” Van Wyk said. For example, Thunder Creek’s MTT trailer can hold up to 920 gallons of diesel fuel and 100 gallons of DEF in a closed system. They also have a smaller 50-gallon DEF skid tank for pickup trucks that is also equipped with a closed handling system.

Van Wyk warns that beyond paying attention to your machine’s efficiency, there’s no way to test for DEF contamination, beyond a $1000 sample sent to a lab. So, the best way to combat contamination is education and proper handling.

“Most of these issues—like shelf life and contamination–aren’t a big deal if you understand the material and implement the right practices,” Van Wyk said. “It’s just a matter of being educated and intentional about how we manage and incorporate DEF into our businesses.”

—

4 Ways Your Tier IV Final Engine Can Change Your Maintenance Routine

Now that you know how to handle DEF any time of year, it’s important to know how things might change when it comes to maintaining your Tier IV Final engine. Here are four things you may need to do differently on your Tier IV Final equipment.

1) More sensors, more potential problems

“On Tier IV Final machines, there are quite a few more sensors and more emission control modules that are distributed throughout the engine compartment—most of which have to be incorporated into our harnesses,” said Robert Bauer, with Carlson Paving Products. “All of the new sensors are for components that didn’t exist at previous tiers, so there are just plain more parts to go bad, more wires to have bad connections, etc.”

Additionally, in Carlson’s case, these sensors are installed by the OEM, so the likelihood of routing inconsistencies that could lead to a failure is higher, he added. “If it was a Cummins engine and a certified Cummins mechanic comes out, each piece of equipment is different,” Bauer said. “Before, all the sensors were on the engine and in the same relative places. Now, with components scattered through the engine compartment, it takes techs longer to orient themselves in a particular piece of equipment.”

Bauer recommends inspecting harnesses and connectors more frequently to look for tightly pulled or fraying wires, damaged connectors, broken connector locks, etc. “It’s more important than ever,” he said.

However, according to Roadtec Service Manager Joshua Jones, any issues with the sensors will still provide the operator with a code to make it easier to find sensors that are acting up.

2) DEF is corrosive (for some materials).

“DEF is caustic and will damage or destroy paint if not cleaned,” Bauer said. So, it’s important to clean up spills promptly. Bauer also recommends inspecting the brackets under the DEF tank for corrosion periodically.

If you spill a small amount of DEF, you can wash it away with water or simply wipe it up. If the DEF is left to dry, it will turn into white crystals that can also be washed away with water. However, if you spill a significant amount of DEF, it’s important to call your DEF supplier for advice on how to handle it.

Although DEF can corrode materials like carbon steel, aluminum, copper and zinc, it isn’t toxic and wearing protective clothing is not necessary when handling DEF.

3) Beware of new engine service procedures.

According to Bauer, many of the new engines have “oil life” counters built into the software that need to be reset when the oil is changed.

“Just like new cars, the check engine light will come on if the oil life counter isn’t reset,” he said. If you ignore the warning on your paving equipment, your machine will go into derate mode. If the crew doesn’t know the cause, they might need to call in an engine service tech for this preventable issue.

To make sure you fully understand engine service procedures, including how to reset your oil life counter, Bauer recommends thoroughly reading your operator’s manual.

“That’s always been a good idea, but more so now than ever,” he said. “Anybody can do this and it doesn’t require special tools, you just need to know what exactly to do.”

4) Change the filter at proper intervals.

“The diesel particulates filter is capturing soot,” Jones said. “When you do your regeneration, it cooks out all the soot. But at a certain point, all the soot buildup that hasn’t burned off starts restricting your power.”

He recommends changing your diesel particulate filter, or DPF, every 5,000 hours.

“You can either service them at an engine manufacturer,” Jones said, “or you can replace it with a new one.” In his experience, DPFs cost anywhere between $3,000 and $8,000.

“That’s just the world we live in now with the exhaust filters,” he said. “But, the truck industry brought everything up to speed before the equipment world got involved, and that really helped.”