Paint it Black and Don’t Look Back

BY Sandy Lender

I type this headline with tongue in cheek because of course asphalt contractors look back at their pavements. We look back with pride, and double-check densities and smoothness. One of the wonderful aspects of being an asphalt contractor is the instant gratification of seeing a job well done at the end of the day. Not only does a smooth, black ribbon of roadway look gorgeous, it’s environmentally sound. Let’s look at just one section of the science behind that statement.

In the draft report Reducing Urban Heat Islands: Compendium of Strategies, Cool Pavements, the authors described albedo as “the percentage of solar energy reflected by a surface,” and go on to say most of the research done on “cool pavements” had focused on the property of albedo.

I found parts of the Strategies document somewhat problematic, but the National Center for Asphalt Technology (NCAT) offered an excellent summary of albedo in its online newsroom:

“Albedo is computed as the ratio of solar energy reflected to solar energy received, and therefore is a unitless value. A material with high albedo (a value closer to 1) reflects more solar energy, whereas a material with low albedo (a value closer to 0) absorbs more solar energy. Typically, a lighter color is more reflective than a darker color. Thus, newly constructed concrete pavements have a higher albedo than newly constructed asphalt pavements.”

Photo courtesy National Asphalt Pavement Association, Lanham, Maryland

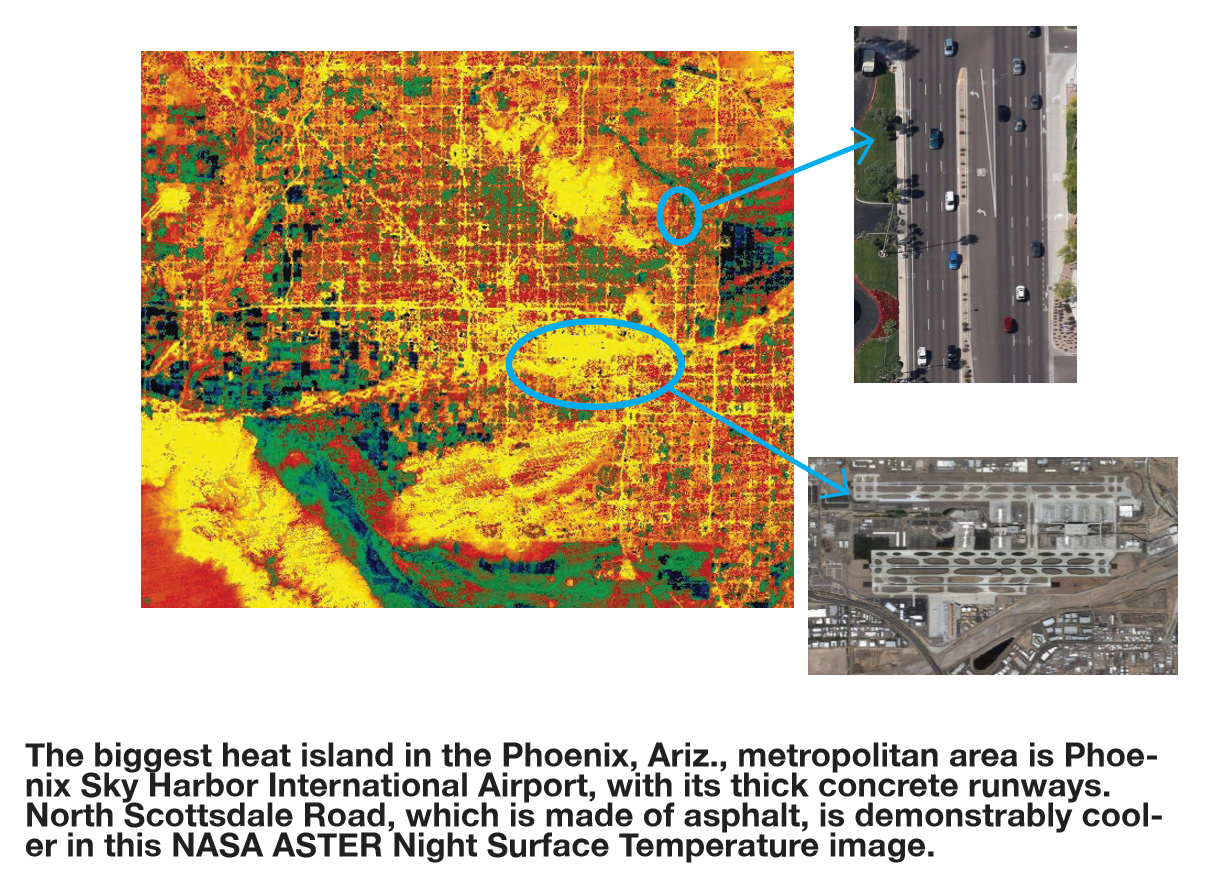

I could not find within the Strategies document information on the detrimental effects of reflecting solar energy onto structures in the built—or urban—environment. In 2013, the researchers at Arizona State University called this phenomenon “unintended consequences.” Energy that reflects off of a light-colored surface doesn’t bounce directly back to the sun; it reflects at an angle onto an object nearby. I encourage you to read the white paper, Unintended Consequences, A Research Synthesis Examining the Use of Reflective Pavements to Mitigate the Urban Heat Island Effect, which was sponsored by the Arizona State University National Center for Excellence for SMART Innovations, here.

The authors of the white paper pointed out light-colored roofing materials can hinder the efficacy of rooftop air conditioning (and other electrical) units. By reflecting solar energy from high-albedo sidewalks, parking lots and roadways, city planners could be unintentionally increasing UHI effects through simple geometry. The authors stated:

“Subsequently, the increased temperature makes air conditioning units work harder, accelerates the heat aging of the membrane, damages surrounding building components, and causes heat discomfort for pedestrians. This effect causes potential problems for the high-density urban areas where building components are in close proximity to each other (Li, 2012). For example, increasing the albedo from 0.15 to 0.5 would substantially impact the comfort of people standing on the more reflective pavement, increasing the temperature they feel by 3 to 6oC (Lynn et al., 2009).”

Well-meaning researchers have suggested in a number of articles and blogs that painting a pavement surface, or even white-topping it, can reduce UHI effects. They’ve gone so far as to suggest white-topping be a new practice, ignoring the heat damage and glare from reflected solar energy. Math and science are teaming up to prove there is a better option: lower the albedo of the pavement to lower the temperature of the city. It looks like we can keep using asphalt to keep things cool overall.

Stay safe,

Sandy Lender